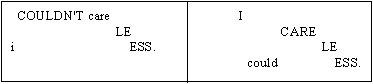

Consider an alleged atrocity committed by today's youth: the expression I could care less. The teenagers are trying to express disdain, the adults note, in which case they should be saying I couldn't care less. If they could care less than they do, that means that they really do care, the opposite of what they're trying to say. But if these dudes would stop ragging on teenagers and scope out the construction, they would see that their argument is bogus. Listen to how the two versions are pronounced:

The melodies and stresses are completely different, and for a good reason. The second version is not illogical, it's sarcastic. The point of sarcarsm is that by making an assertion that is manifestly false or accompanied by ostentatiously mannered intonation, one deliberately implies its opposite. A good paraphrase is, "Oh yeah, as if there was something in the world I care less about."

4 comments:

Absolutely true! In Portuguese there's a not so recent sentence that has exactly the same scope:

«Ralo-me muito com isso!»

It means «I worry a lot about that» and seems to have the same use: you say it whenever you mean «I don't give a damn about that»...

There's definitely a UG! Long live Chomsky!

Estás de acuerdo?... (Lol!)

... I don't mean to bother you, but a doubt came to my mind as I was reading one of your posts.

"The same goes for pronunciation, because if a critical period exists for the acquisition of it, this will point, in my opinion, to a set of innate capabilities different from those underlying UG."

I'm sure you've heard/read about the so-called "perceptive gradual deafening process". Roughly, it postulates a young child "hears" every possible speech sound there is, and is thus able to produce them all as well. As s/he acquires all the oppositions relevant within his/her mother language's phonological system, s/he gradually becomes deaf to any other oppositions. An example: the [ç], as in German "ich" or in Swedish "kärlek"; every Portuguese child utters it at some point of his/her acquisition process, but soon it will be replaced by [∫]. Now, curiously enough, adults will utter it too, if they want to imitate the language of a child, but if they're learning German they'll pronounce "ich" as [i∫], rather than [iç]… So it seems to me the UG works phonologically as well. Am I wrong?

Thanks a lot!

Hi Ric!

I don't know, really. I read this article (Mehler et al. 1988) in which they did an experiment with several 4 day old French babies. They measured the rate at which they sucked a pacifier connected to a computer while exposing them to streams of alternative languages. The babies could, for instance, distinguish between french and other languages, and even between pairs of languages that were not spoken around them, like english and italian, or japanese and dutch. Weird thing is, at two months they had lost this second ability. They could still distinguish french from other languages, but not so easily other languages among themselves.

Is this the perceptive gradual deafening process you were referring to? Children do seem to tune into the language they're learning, picking out the contrasting sounds in it, turning off and on the "switches" that will eventually make them native speakers of their language. That's why when we are older, we find it so difficult to correctly reproduce in a second or third language the sounds used by their native speakers (english vowels still give me a headache!).

In any case, you're right. What i should have said in my paper is that the rules and parameters underlying pronunciation are probably a different set of those underlying syntax, even though both are part of the language instinct advocated by Pinker. I just hadn't thought of equating that concept with UG; i was thinking of UG is a subset of the language instinct, including perhaps those rules and parameters that underlie phonology and syntax... Fuzzy thinking, because it's all in the same continuum, obviously. For instance, it's been shown that it's possible to learn what kind of language a baby is learning by the qualities of the babbling s/he produces at 10 months of age, even when there is no meaning behind the sounds (forgot where i read this, but i did read it!).

I'm sure my professor will point this out when she gives me back my essay. UG(h)!

Thank you for your interesting comments and kind questions, Ric :-)

I really appreaciate them. By the way, YOU know a lot about linguistics, don't you? Unlike myself...

Thank you for your response, Mariano! Most kind of you!

I think I can now say that I devoted my ear to languages, since music was then out of reach (for my parents it was, of course, since they couldn't afford such an education for me.) As I've always liked explanations, knowing foreign languages and reading their literatures seemed not enough to me... And then I discovered linguistics - love at first sight! I've lectured (!) on Portuguese phonetics, phonology and morphology years ago, but the Portuguese academic environment didn't «suit» me, so to speak...

The linguistics I know is now oldfashioned, but I still manage to swim among concepts, I think...

It's really like an old passion: whenevr I meet someone in that area, I just cannot resist...

I only hope I haven't bothered you, now that you're looking for a new path...

I wish you «muchas felicidades»! (this must be «portuñol» for sure) (Lol!)

Post a Comment